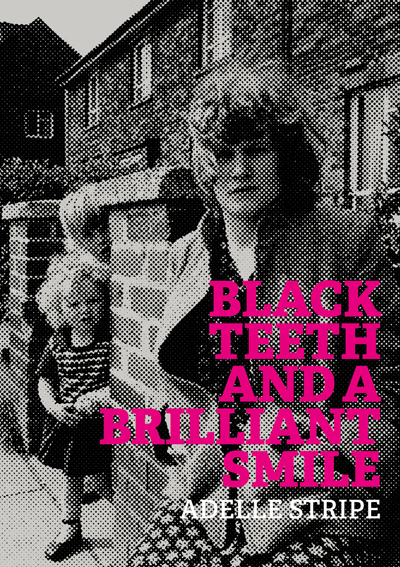

Black teeth and a brilliant smile…

I struggle to read books these days. Too many days/nights staring at a blinking cursor on the laptop screen. Eye muscles that give up after four pages. Too much life, not enough down time. The ageing process making me doze off. It’s a rare novel that enables me to get through from start to finish in less than a year. Adelle Stripe’s debut novel Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile is that rare thing. A single sitting was all that was required to get through a superb piece of literature that blurs the real and the imagined and is inspired by the life and work of the dead-too-young Bradford playwright Andrea Dunbar.

As ever, when scrawling my thoughts on the output of Hull-based publisher Wrecking Ball Press, I’ll declare an interest – editor Shane Rhodes and the WBP team are mates of mine. Shane threw me a proof copy of Black Teeth… and, for the first time ever having filled my shelves with Wrecking Ball books, told me to write something about it. I also met Adelle recently and a dodgy transaction outside a city centre hotel involved her handing me the necessary documentation to gain entry to John Grant’s North Atlantic Flux festival, which had brought her to Hull on this occasion. So, I did put off reading this book for a few weeks because, although everyone that had read the manuscript had told me how bloody marvelous Black Teeth… is, I didn’t want the freebies and the friendships and my general love of everything WBP to balls up my effort at critique.

I probably shouldn’t worry about these things. No other fucker does. Although do feel free to doubt my impartiality, or lack thereof.

Black Teeth is a rollicking journey, which is just what my eyes and mind require these days, through the really tough life of a genuine working class hero. Quite where fact meets fiction I don’t know, because I’ve not done the level of research that Adelle clearly has (made clear in a PhD kinda way by the inclusion of a bibliography at the rear of the book), nor does it matter. The words on the page simply bolt along at a tremendous, breathless pace. And then, and then, and then… You just have to keep going, keep turning the pages, and be with Andrea Dunbar all the way from Buttershaw to the Royal Court, the big screen and back in the boozers on the estate.

There’s no airbrushing of Dunbar – this portrayal is pretty warts and all – but you will close the cover feeling a tremendous amount of sympathy for the woman. While she may well have fucked it up by pissing it all away, Dunbar was also let down by an industry that, even now, feels no duty of care for the authentic voices it hoovers up in order to serve itself. Dunbar was a victim and that much is clear. She was fucked, fucked over and fucked up by men and, while that generated some material, it also left her without the tools to cope when she did garner attention with first play The Arbor. That, and the fact that she was in a permanent state of skint when writing, when not writing, and while simply trying to navigate life, three kids an’ all.

Adelle serves up this overwhelmingly tragic life story against a Bradford, like much of the north in the same time period, that was falling apart. Except Bradford was darker back then, because the Yorkshire Ripper was driving about with his hammer on the passenger seat, and racial tension was heading towards boiling point, and, well, it’s Bradford, isn’t it. A fucking depressing place covered in industrial grime at the best of times.

Dunbar was different. She had a talent that should have allowed her to escape her predestined life in slum accommodation. It was a talent that was spotted by others and sent the way of Max Stafford-Clark at the Royal Court. Dunbar’s journey from Upstairs to Downstairs didn’t take long and, indeed, it looked like the trajectory only had one direction. She was taking flight. The only way was up. Drink though, innit? Why pull your fucking hair out and give yourself a massive headache crafting plays when you can get a round in down the local. After all, they gave you all the dialogue so you should get them a pint. And yourself a drink and another one and another one ad infinitum.

While whistling through the pages of Black Teeth…, even though the end is nigh right from the off, the hope is that a hero will step in and throw his or her arms around Dunbar. It wasn’t Stafford-Clark, who gave up on Dunbar in light of her drinking and draft-dodging to move on to his next favourite hot new thing, and it certainly wasn’t Alan Clarke, director of the film version of Rita, Sue and Bob Too. And sadly Kay Mellor arrived on the scene just too late.

Never able to stash enough cash back to get away from Buttershaw, writing becoming too big a pain in the arse and head to deal with, and with too complex a life to actually give a shit about what a bunch of middle class tossers in theatre, tv and film thought of her or turn up for meetings with them, an end to the writing and an early death, in retrospect, was inevitable.

But what Adelle’s book underlines is how difficult it is to write your way out of the hand that you’re dealt. For all of her skill and talent with words, and ability to honestly depict the life of the working class communities that were hurled on the scrapheap in Thatcher’s Britain, Andrea Dunbar didn’t know how the hell to deal with the daily grind. She didn’t help herself, that much is clear. But nobody else helped her either. And there were many in a position to do so along the way. It may not have stopped the brain haemorrhage that resulted in Dunbar’s death at 29 but it may well have made life more bearable while she was still living it.

Original voices from places like Buttershaw – and there are many places like the Buttershaw of the 1980s still, even in 21st century Britain – who draw from terrible life experience and get those stories on stage shouldn’t be allowed to fall by the wayside; they’re vital.

Adelle Stripe’s book is a wonderful 158 page story. It’s an incredible insight into the life of Andrea Dunbar, whatever the blurry lines between fact and fiction. Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, like Dunbar herself, makes no apologies and there’s no bullshit within. Adelle’s depiction of Dunbar’s life feels every inch as authentic as its subject matter undoubtedly was. The author’s research interests include “northern working-class culture, the non-fiction novel and the literary north.” Black Teeth… sees Adelle roll all three of those interests in one and the result is nothing less than magnificent.

Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile is published in July 2017. It can be pre-ordered directly from Wrecking Ball Press.